-

-

-

Cicely Hey (1896-1980)

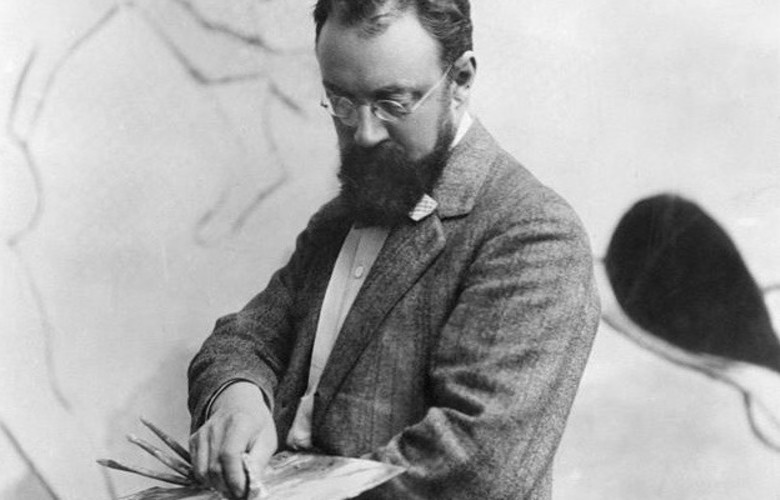

A biographical survey by Alison BennettA painter, sculptor, illustrator, designer and model maker, yet today Cicely Hey is chiefly remembered through her association with Walter Sickert, both as a model and as a friend. Less well documented, however, is the wide-ranging work Hey produced over the course of her lifetime. A recently discovered collection of a significant number of her paintings, drawings, watercolours and prints has prompted this exhibition and a re-evaluation of the life and work of this hitherto neglected artist. Cicely Hey c. 1906

Cicely Hey c. 1906Mary Cicely Hey was born in 1896 into an affluent family in Great Faringdon, Oxfordshire, the younger daughter of a surgeon, Harold Darwin Hey and Mary née Mallam and she appears to have enjoyed a happy childhood. Her early years were spent in a large household which included her father's business partner, a governess, a cook, a housemaid and a pageboy. Local press reports reveal the family's involvement in village life; Hey and her sister organising fundraising sales and appearing in amateur theatrical entertainments. Later, they both attended school in London, living in Hampstead with their maternal uncles, the household also including a visiting art student who may well have sparked Hey's artistic ambitions.[i]

Cicely Hey 1923, ink by Walter Sickert (The Whitworth Art Gallery)

Cicely Hey 1923, ink by Walter Sickert (The Whitworth Art Gallery)Hey's earliest known drawings can be found in a sketchbook of 1913 which she compiled while studying at a boarding school in Brussels.[ii] The sketches record the various activities offered at the school, which, unusually, appear to have included life drawing classes. Many of these sketches show early signs of Hey's later drawings, often with figures viewed from behind, absorbed in an activity or simply resting as if unaware of the artist's presence, Hey preferring to remain inconspicuous and unobserved, an approach much favoured by Sickert.[iii] In fact, scarcely any photographs of her as a young woman have been uncovered; her features familiar largely through the portraits Sickert painted of her and her own self-portraits. Subsequently Hey became a student at the Central School of Art in London followed by a year (1919-20) studying painting and drawing at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London under the renowned Slade Professor Henry Tonks.[iv] Her family clearly disapproved of Hey's choice to become an artist; a close friend recalled a story Hey related of her father instructing Hey to take a bath with carbolic on returning from college because of all the 'unpleasant and odd people' she had been mixing with! In his biography of Walter Sickert Denys Sutton refers to a visit Sickert made to Hey's family in support of Hey's artistic ambitions, dressed in his 'Sunday best' and using his charm to reassure them.[v] However, her family's concerns clearly did not deter her.

Cicely Hey and Robert Tatlock with Tatlock's niece and nephew, 1925

Cicely Hey and Robert Tatlock with Tatlock's niece and nephew, 1925By 1920 Hey's family had moved to the London suburbs, but Hey, valuing her independence and exhibiting an underlying rebellious streak in her character, chose a more bohemian lifestyle, taking a room in a shared house at 19 Taviton Street which Sickert biographer Matthew Sturgis described as 'living - literally and figuratively - on the fringes of Bloomsbury'.[vi] The house was owned by the author Margaret Bulley (Hey's portrait of her was later included in the Art Celebrities exhibition), the household comprising several illustrious occupants among whom Hey's future husband Robert Rattray Tatlock, writers David Garnett and Ethel Sidgwick,[vii] and artists Florence Klein and Lettice Cautley Baker[viii] could be counted. Tenants came and went; Hey and Tatlock relocating to a small flat in Primrose Hill when they married.[ix] In a 1923 sketchbook Hey recorded her not only her fellow tenants but also the many visitors to Taviton Street, whose identities will require further research. One can only imagine life at no.19 and its effect on the young Cicely Hey whose circle of friends and acquaintances grew rapidly to include some of the most important intellectuals, philosophers and artists of the early 20th century.

While Hey's friendship with Sickert has been documented by several of his biographers, it is worth repeating the circumstances of their first meeting and how, in Hey's own words, their relationship developed. Hey first met Sickert early in 1923 when she was selling tickets to a lecture on 'Art' given by Roger Fry at Mortimer Hall which Sickert attended. He asked her to sit for him the very next day, clearly taken by, as he later described, her 'funny little beautiful sane dear face'.[x] Sickert's wife, Thérèse Lessore, agreed: 'you've got just the kind of face he likes to paint'.[xi] During a radio interview broadcast by the BBC in 1961,[xii] Hey recollected that she visited Sickert nearly every day for a year or more, always by telegram invitation, admitting that she was desperately shy and did not speak much for fear of not being asked to sit again. This suited Sickert who would, laugh, sing and tell stories during these intimate sittings, entertaining his audience of one and prohibiting any other visitors to the studio while he was working by locking the door, initially causing the rather timid Hey some concern. She recalled how she would leave his studio her 'sides aching with laughter' describing how Sickert fondly called her his 'mascot', nicknaming her 'Kikely', and reflecting that she was probably the last to pose on Sickert's trademark iron bedstead in the Fitzroy Street studio, seen in many of his paintings. Some years later Hey wrote to art dealer and art historian Lillian Browse, 'but you will have gathered that I wasn't just a girl who happened to have the kind of face Walter Sickert liked drawing and painting, but a very close friend and one of the very few artists who were allowed behind his 'iron curtain' of locked studio doors'.[xiii] The charismatic Sickert already in his 60s and the much younger and outwardly shy and reserved Hey undeniably made for an unusual pair, Sickert often taking Hey with him on walks around Islington in search of inspiration, where he would talk and sing to anyone he met, much to their amazement. Hey regarded Sickert foremost as an artist, someone whose advice she valued, and commented that one hardly ever got to know Sickert the man. She acknowledged that he treated her with the greatest affection and generosity and in 1924 he stood as one of the witnesses to Hey's marriage to Robert Rattray Tatlock. Hey recalled Sickert painting seven portraits of her during 1923 and they remained great friends and correspondents for many years.

Cicely Hey by Walter Sickert, 1923 (The Whitworth Art Gallery)

It is worth exploring the few glimpses of Cicely Hey's early career that can be gleaned from exhibition reviews in national and provincial newspapers and through her participation in artists' societies. Now identifying herself simply as Hey, she regularly exhibited in London during the 1920s and 1930s. She first exhibited a portrait with The London Group in 1923 and was elected to full membership in 1927, exhibiting four works that year: The Red, Red Rose, The Green Scarf, Bath Time and The Professional. At The London Group's retrospective exhibition in 1928, she showed a painting, titled The Model. Hey continued to exhibit with The London Group every year until the outbreak of the Second World War and on occasion during the post-war years, remaining a member up until her death. Hey's work reaped some modest critical success. In 1930 she showed a work titled Reflection at the first exhibition of the Young Painters' Society at the New Burlington Galleries which was mentioned in The Times.[xiv] At the third exhibition of the National Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers and Potters, held at the Royal Institute Galleries in Piccadilly in 1932, The Times gave special mention to her work The Child.[xv] In 1934, Hey's watercolour, At Her Dressing Table, exhibited with the same society, was considered by The Times one of the 'more genuine' paintings there.[xvi] At the exhibition of The London Group later that same year, Hey exhibited six watercolours, one of which, Cabaret Girl, possibly inspired by Sickert's fascination for the theatre, was picked out by The Observer as 'interesting',[xvii] and, while The Scotsman's art critic was not enthusiastic about the exhibition, he highlighted Hey's watercolours as 'pleasing'.[xviii] The reviewer for The Hull Daily Mail, described a later London Group exhibition as 'provocative' but selected Hey's drawing of Sir Henry Wood as 'straightforward… [and] set in strange company'.[xix] Other works by Hey were shown with the Women's International Art Club, the New English Art Club, the Society of Graphic Artists and at the No Jury Art Club exhibition organized by Sickert and held at London's Whitechapel Gallery in 1929 where she exhibited three oils titled Betty, Nellie and Trust. Sickert too approved of her work 'Your little canvases are ripping… my missus agrees with me'.[xx]

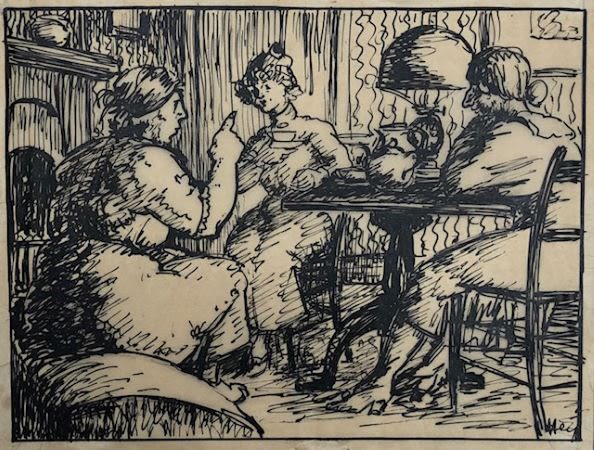

Mother and Child c. 1923, ink by Cicely Hey, (Private collection)

Mother and Child c. 1923, ink by Cicely Hey, (Private collection)Hey's sketchbooks reveal the wide-ranging subjects from which she drew inspiration. While at the Slade she produced many life drawings and her sketchbooks at this time are also full of examples of calligraphy as well as detailed pattern designs. Hey made many charming and intimate portrait sketches of her friends and of her friends' children, often in repose, exhibiting the loose and spontaneous style seen in her later Art Celebrities portraits; her sensitive drawings of mothers with their young babies are particularly captivating. Hey also found the countryside a constant source of ideas to work with and develop; her sketches and finished work including identified landscapes both in England and in Europe.[xxi] In addition to rural landscapes her sketchbooks contain many drawings of agricultural scenes with farmyard animals skillfully rendered, often, by necessity, very quick line sketches which she repeated over and over again in order to capture movement, many of which she later worked up into colour illustrations. Her linocuts depicting zoo animals are bold and expressionistic, filling the whole picture frame. One can imagine Hey had a young audience in mind for these prints and drawings; her sketchbook from 1921 contains an alphabetical list of animals for which she subsequently produced small prints.

Pigs 1922, watercolour by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

Pigs 1922, watercolour by Cicely Hey (Private collection) Tiger and Cub 1922, linocut by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

Tiger and Cub 1922, linocut by Cicely Hey (Private collection)Hey's drawing of a woman knitting, one of her many compositions depicting contemplative figures in a domestic setting engaged in quiet activity, clearly shows the influence of earlier works such as Sylvia Gosse's The Sempstress and Harold Gilman's Interior with Woman Sewing, both from 1913,[xxii] each a contemporary scene of domesticity. Hey would have been familiar with the work of the English Post-Impressionist Camden Town Group, (Gilman was one of its founder members), through her friendship with Sickert and may well have visited one of the only three exhibitions of their work held in London during her teen years. While many of Hey's drawings are of friends or 'celebrities', her painting titled Orders for Dinner portrays a working woman, taking a rest from her duties, a further example of the depiction of modern urban life typical in the work of the Camden Town artists. In the few known paintings by Hey, her use of a soft yet vibrant colour palette is reminiscent of the work of Robert Bevan, another of the founder members of the Camden Town Group and of The London Group. In marked contrast to the urban realism of Sickert's earlier interiors comprising dark and sombre earth tones, Hey presents a more pleasing view of everyday life in both her interior and outdoor compositions with her use of light and colour; her broad brush strokes expressive and confident.

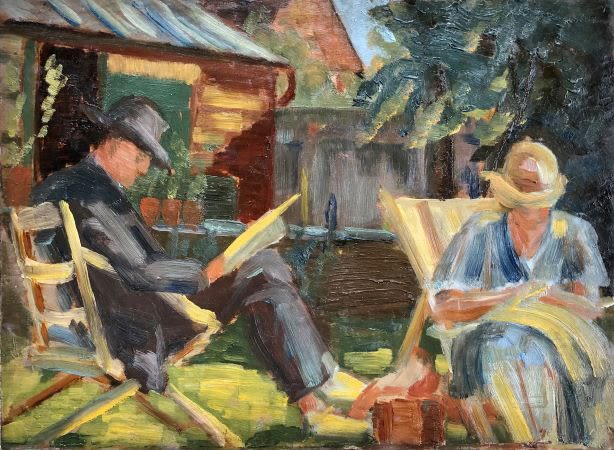

Reading on The Terrace c. 1924, oil on panel by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

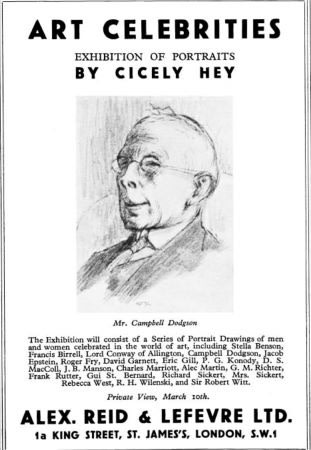

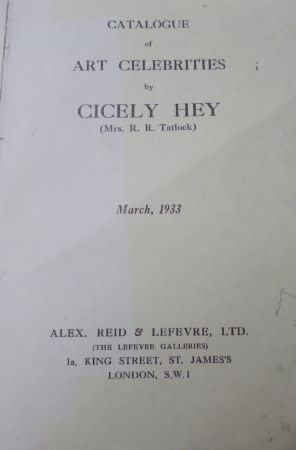

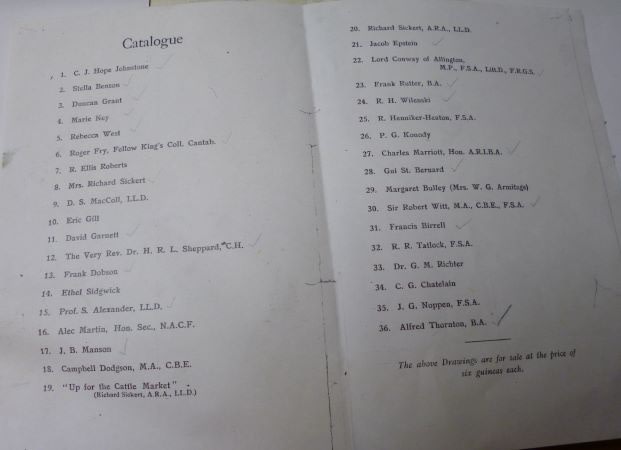

Reading on The Terrace c. 1924, oil on panel by Cicely Hey (Private collection)In March 1933 The Burlington Magazine published an advertisement for an exhibition of portraits by Cicely Hey, her first solo exhibition. The works were being shown at the fashionable London gallery of Alex. Reid & Lefevre, a gallery specialising in Impressionist and modern art. The exhibition, titled Art Celebrities, consisted of 'a series of portrait drawings of men and women celebrated in the world of art', and represented among them a number of artists including Walter Sickert and Thérèse Lessore as well as names associated with The Burlington Magazine, both as contributors and members of its Consultative Committee. Hey had a personal connection with the Burlington: her husband was its editor. The anonymous reviewer for The Times, commenting on Hey's choice of subjects, stated that she not only painted portraits of artists but also of 'the lesser breed whose lot it is to write about it in the papers',[xxiii] among whom her husband could be included. The reviewer continued, describing Hey as 'distinguished as an artist by liveliness and sensibility' picking out several portraits for particular praise including that of the artist, and friend of Sickert's, Alfred Thornton. Sickert, too, congratulated her on her 'splendid drawing of Roger' [Fry], adding that he 'looks like an ecstatic carp, which he did, poor dear, to the joy of us all'.[xxiv] It is interesting that The Times later made reference to the exhibition in its obituary for Tatlock, acknowledging that Hey was 'a talented figure and portrait painter' and that in the exhibition, which had taken place more than twenty years earlier but clearly still remembered, Hey had 'enlivened the journalism of art'.[xxv]

Duncan Grant c. 1933, ink by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

Duncan Grant c. 1933, ink by Cicely Hey (Private collection)We can glean some idea of her style from the Art Celebrities portrait sketches which make use of rapid drawing, some with delicate hints of colour and shading, whereas others are simply line drawings. They display strong psychological definition, and capture each sitter's facial expression with little concern to flatter or soften any imperfections; indeed Tatlock's obituarist somewhat unfairly referred to her drawings as 'semi-caricatures'.[xxvi] The reviewer for The Birmingham Daily Gazette commented on the exhibition's 'more varied and eccentric view than the average collection of sitters…' and suggested that 'the artists can have their revenge: they can all set to work to portray Miss Hey as they see her'.[xxvii] Of the thirty-six drawings exhibited, ten are now in public collections in London and Manchester, and several of the remaining works are now with dealers or in private ownership.

Walter Sickert Sketching, c. 1924, ink by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

Walter Sickert Sketching, c. 1924, ink by Cicely Hey (Private collection)Hey's ability to produce accurate likenesses is borne out in a letter from Sickert's wife Thérèse Lessore thanking Hey for a drawing of Sickert she had sent. She wrote, complimenting Hey, 'I think it is an excellent likeness and also gives an expression that I know very well and I do not think has been put down by either hand or photograph before'.[xxviii] Furthermore, Tatlock's niece remembered as 'marvellous' a celebratory sketch Hey had produced, (sadly lost), simply from memory and a few photographs, of a dozen or so members of the Tatlock family, including their pets.[xxix] Other portraits recently uncovered include such celebrated figures as composer Arnold Bax, conductors Sir Adrian Boult and Sir Henry Wood (the latter reportedly drawn during the interval at one of the 'Proms'), as well as the author E.M. Forster each adding to an already impressive list of such key figures of the 20th century whom Hey was able to call upon to sit for her. These names provide testament to Hey's reputation as an artist, no doubt, in part, due to her friendship with Sickert and to members of the Bloomsbury Group among whom she had many acquaintances.

After Sickert's death in 1942, Lessore wrote to Hey (always as 'Mrs Tatlock') thanking her for her condolences and commenting 'I know you valued my husband's friendship very much'.[xxx] It is clear Sickert valued Hey's friendship too; Richard Shone, in his 1988 biography of Sickert[xxxi]suggests that Hey was 'of inestimable value' to Sickert, who had been greatly affected by the death of his second wife. Hey received many requests from writers and art historians for her recollections of Sickert whom she describes in a draft letter 'like a valuable diamond' with 'very many facets' adding that only those he knew intimately would be rewarded with more than just one facet.[xxxii] In the letter Hey dismisses much of what others had written about Sickert, including artist and Sickert biographer Marjorie Lilly, but is more generous in her comments about Sylvia Gosse, a close friend of Sickert's, who became co-principal of the art school he had set up in Hampstead. Her strongest criticism is left for Lillian Browse whose views on Sickert Hey finds extraordinary, especially as Browse had never met him; '…she told me she was glad she hadn't.'

Hey continues that Browse had suggested that Hey had been an 'actress seeking publicity' (perhaps calling to mind Sickert's portrait of Hey which was later titled The Actress), and she describes how difficult it had been to convince Browse that she had never been on the stage and that she had already been an exhibiting artist when she first met Sickert.[xxxiii] Hey vigorously but somewhat naively dismisses Browse's view of Sickert as a philanderer although admits that no doubt several women loved him. Conceivably Hey had cause to feel ill-disposed towards Browse given Browse's rather negative comments about 'her' Sickert. Hey also corrected Browse's mistaken conclusion that Sickert's portraits of Hey were painted directly on to canvas; Browse clearly unaware of the preparatory sketches Sickert had given to Hey.[xxxiv] Browse makes no reference to Hey in her biography of Sickert [xxxv] despite a request she recalled having received from a Dr de Neumann to include in her text the 'important part played by Cicely Hey in Sickert's artistic life'. While neither Browse nor Hey could remember such a person, it offers yet another indication of the significance of Hey's friendship with Sickert during his later years.[xxxvi] Other notes show that Hey was not impressed with Denys Sutton's biography of Sickert either, accusing him of 'too little research'[xxxvii]

The Conversation c. 1924, ink by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

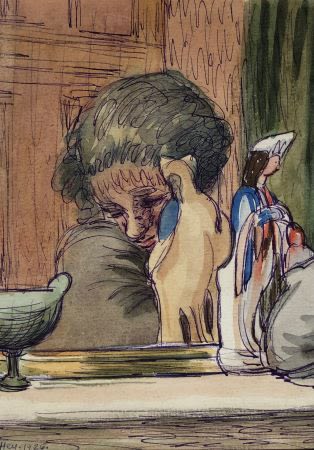

The Conversation c. 1924, ink by Cicely Hey (Private collection) The Mantlepiece (Self Portrait), 1925, watercolour by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

The Mantlepiece (Self Portrait), 1925, watercolour by Cicely Hey (Private collection)Although Hey was never a pupil of Sickert as such, he would freely offer advice during their sittings. Drawing was crucial to Sickert and an integral part of his practice and his influence can be seen in many of Hey's works. In 1930, The Manchester Guardian published a series of articles on Sickert's recommendations for drawing, advising firstly to draw the outlines lightly, looking at both object and background at the same time. Then to add shadows, and finally to go over it all again with the point of the pencil making further corrections, without any rubbing out.[xxxviii] While Hey's early drawings are mainly in pencil and some with splashes of colour, many later examples demonstrate where a pencil drawing has been drawn over in black ink, emphasizing the composition as well as making any necessary corrections, following Sickert's advice. The mirror motif, much used in Sickert's paintings, including a double portrait sketch which Sickert mockingly titled Death and the Maiden after Hey commented on his age,[xxxix] also found its way into Hey's work. In a drawing of 1929, Hey's own image can be seen behind the reflection of the seated figure she is sketching adding depth and interest to the composition and demonstrating her skill. A further example, Orders for Dinner, mentioned above, includes another double reflection in the mirror behind the seated woman. Hey exhibited several works both with The London Group and elsewhere with titles such as Reflection, At Her Dressing Table, At Her Mirror and Through the Looking Glass all of which clearly suggest similar compositional themes. Many of Hey's re-discovered sketches have been squared up (following 'the Sickert method'[xl]) for larger or more finished works and some related drawings, illustrations and designs have now been identified. Sickert instructed Hey in the use of photography as a means of developing ideas for her paintings (although there is no evidence she ever did so) to 'notice the setting of one thing against another'.[xli] Sickert had started to use photographs in preference to sketches although Hey remembered that he hadn't really known how to use the camera he had bought.[xlii] Sickert also encouraged Hey in her printmaking, with practical demonstrations in techniques such as etching and engraving, using his own work as an example,[xliii] many of Hey's prints still surviving.

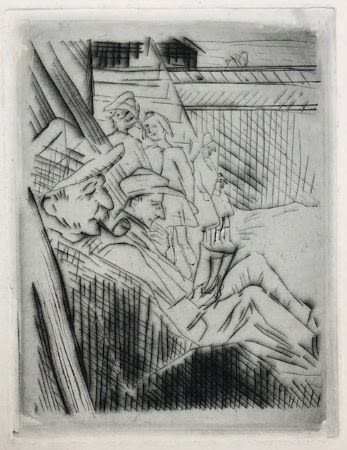

On Brighton Beach c. 1924, etching by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

On Brighton Beach c. 1924, etching by Cicely Hey (Private collection)Hey clearly valued Sickert's advice carefully noting in a diary for 1923 :

"Sickert says : Paint from drawings. Prepare canvas with china clay, on the top of which put a coat of size - so that surface is granite like. For large pictures paint on this with thin paint and no medium. For small sketches use paint mixed with medium put on very thin. When painting from a drawing square up drawing and canvas then decide whether in painting lights are to be warm and shadows cold or vice versa. Paint on canvas enlargement of drawing blocked in in two colours (pink and blue or any light colour), one being hot the other cold - let this dry then finish painting on top using thin paint and no medium. Mix up all the colours and tones to be used in a painting before beginning, and use nothing else until painting is finished. Quality is got by scraping paint thinly onto canvas, not with blobs of thick paint. There should be as little 'écartement' (splits) as possible in a picture. "

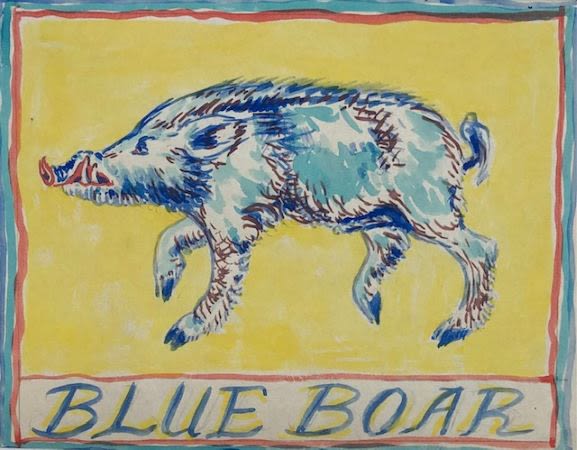

Design For Pub Sign 1936, watercolour by Cicely Hey (Private collection)

Design For Pub Sign 1936, watercolour by Cicely Hey (Private collection)As an accomplished designer and illustrator, Hey participated in the hugely successful Inn Signs Exhibition held in 1936 at the Building Centre in Bond Street, in the heart of London's art trade, the first and only exhibition of its kind. It was reported that 10,000 visitors attended during the first two weeks and the exhibition was widely reviewed, both in the UK and overseas.[xliv] It had been conceived by the Council for the Preservation of Rural England and the Brewers' Society to promote the art of inn signs and was received with great acclaim. Among the advisory committee were several eminent British architects including Sir Edwin Lutyens. A short film of the exhibition was made,[xlv] the first of its kind to be publicly broadcast, featuring many of the 270 signs which had been lent to the exhibition along with over 150 designs, photographs and engravings among which Hey's design for The White Hart was reported to have been the only design to receive a commission.[xlvi] Interestingly, in one of Hey's earlier sketchbooks, she describes in detail the composition of the National Gallery's Wilton Diptych (NG4451), referencing an article in The Burlington Magazine which she no doubt recalled when planning her design.[xlvii] An undated drawing by Hey clearly relates to the National Gallery's painting and could conceivably be a preliminary sketch for the design shown in a still from the 1936 film.[xlviii] Recent research has unearthed many other inn sign and advertising designs by Hey, along with a number of accomplished and highly imaginative illustrations including several for a children's book The House of Crooks and others for a Christmas story. Other identified work includes a manuscript for The Fogroom Bird, written and illustrated for Hey's niece, which appeared at auction at Cheffins Fine Art in 2014, and the beginning of another story The Pig with the Blue Back. It is probable that Hey simply created these for her young nieces and that none was ever intended to be published.

At the beginning of the war Hey, now divorced[xlix], moved into the Garnetts' home, Hilton Hall near Cambridge,[l] in order to care for her dear friend Rachel 'Ray' Garnett, sending news of Ray's declining health to her husband, David Garnett, then working at the Air Ministry in London.[li] [lii] Hey and Tatlock had been great friends of the Garnetts, fellow tenants at Taviton Street, acting as witnesses to their marriage in 1921. After Ray died early in 1940, Hey returned home but was unwilling to continue living at her widowed father's 'depressing cottage' in Sussex and, in need of an income and as an escape from her failed marriage, she found work as a civil servant, a rather unlikely occupation for such a talented artist. Writing to David Garnett, she described it as an interesting role as a 'chartist and draughtsman in the Statistical and Intelligence Department of the Ministry of Food', initially receiving training in Colwyn Bay in North Wales. In the letter she comments that her boss considered having an artist in the drawing office a great asset, and she describes it as a 'jolly place to work', with much laughter, clearly amused by the obvious disapproval of some of her colleagues.[liii] She joined the Ministry's dramatic society and her sketchbooks from that time reveal several colourful programme designs for their shows and various party invitations.At the end of the war, and still reluctant to return to London, preferring to live quietly in North Wales, Hey began modelling a series of miniature figures in historically accurate costumes, using a variety of materials including terracotta, wire and papier maché, some modelled with moveable limbs. (Hey herself was once described as 'like a toy made carefully out of wires and a little wool'[liv]). These figures would delight any young visitors to her tiny cottage in Llysfaen. In a short film made by the BBC in 1965,[lv]Hey describes the processes involved in creating these detailed figures, undertaking meticulous research consulting old prints and tapestries to ensure the authenticity of each costume, each figure taking as long as two months to complete. She gave them all names, some as family groups, appropriate to the period, taken from a catalogue of brass rubbings. In all she made around forty figures over a period of fifteen years illustrating the history of English costume. Hey's ability in her earlier drawings to create credible and honest representations of the people she knew is reflected in the attention she paid to these miniature figures created from imagination in her later years.

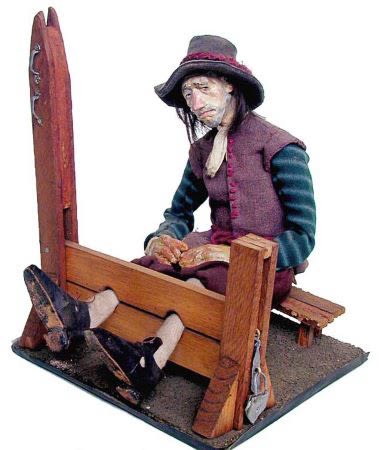

Hey may well have been inspired to begin creating her model figures by John Wright, a master puppeteer[lvi], who had been sharing a house in Fitzroy Street with her friend David Garnett at the beginning of the war. While the popularity of puppetry had declined during the early years of the 20th century, interest had been kept alive by a small band of enthusiasts. The 1923 publication of H.W. Whanslaw's Everybody's Theatre had prompted a revival of this art, and in successive decades many professional puppeteers toured the country with their puppet shows.[lvii] From the late 1940s until the early 1970s, Hey exhibited her model figures extensively in Wales and also in London. Her costumed figures were shown by Waldo and Muriel Lanchester, founders of the London Marionette Theatre, at the Shakespeare Festivals of 1964 and 1969, and her models also made press and television appearances during this time. In addition, they appeared on several occasions during the 1960s at the Royal National Eisteddfod.[lviii] In 1964 an exhibition of thirty-two of Hey's figures, illustrating the history of English costume in fine detail, was held at London's Geffrye Museum, (now the Museum of the Home), transferring to the Colwyn Bay Public Library along with seven additional figures, early in 1965. These, along with another set of 'Bygone Figures' were bequeathed to the National Museum in Cardiff in 1980[lix] where they became part of the Schools' Outreach Programme. An example of such work, Figure in Stocks (1966) is held at the Museum of English Rural Life at Reading University and was included in an exhibition held there in 2007-08

Figure in Stocks 1966, model by Cicely Hey (Museum of English Rural Life, Reading)

Figure in Stocks 1966, model by Cicely Hey (Museum of English Rural Life, Reading)In addition to the costumed figures, Hey regularly exhibited drawings and paintings with local art societies such as the Denbighshire Art Society, an example of which, Reclining Figure, was remarked upon as 'exemplifying her customary poetic line'.[lx] As a sculptor, Hey worked mainly in terracotta and cement fondu, creating small pieces, some inspired by biblical subjects, others depicting family groups and animals. In addition she produced several small terracotta portrait heads. One in particular, Portrait of Bob Hughes, which had been exhibited with The London Group in 1953, was selected by a committee consisting of Alfred Janes, Ceri Richards and Ruskin Spear for the second Welsh Arts Council's Open Series exhibition of Contemporary Welsh Painting and Sculpture, held at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff and the Newport Museum and Art Gallery in 1955. This work was purchased for the Contemporary Art Society of Wales and subsequently donated to the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea. By the 1960s Hey considered herself better known as a sculptor, with some of her terracotta sculptures of animals and a wire sculpture titled Leviathon appearing in exhibitions in North Wales during the 1950s. In her later years Hey continued to work with wire, filling her tiny cottage with 'strange wire objects' as remembered by friends.

Despite a number of personal setbacks, Hey clearly possessed a quiet self-confidence and held a positive outlook on life, a characteristic Sickert valued, noting 'you are so game and make bricks all the time with any straw that comes to hand', remarking on her 'natural gift'.[lxi] One can only imagine how Hey's career might have developed had she returned to London after the war. Her creativity, however, in its many forms, remained constant throughout her life and sustained her through many changes in her circumstances. Hey died in 1980 at her home in Llysfaen, Colwyn Bay, and for many years her work was neglected. However, some twenty-five years after her death, many of Hey's Art Celebrities portrait drawings were brought back together in an exhibition held at Llanover Hall in Cardiff in 2006, curated by Welsh artist, Tony Goble (1943-2007) during his residency there. He described it as 'a unique exhibition for Wales, with both an artistic and historic relevance - and not to be missed. Giving people a rare opportunity to see the work of this important, but relatively unknown artist, whose work has not been on major public display for over 70 years'.[lxii] It is to be hoped that the re-discovered collection of Hey's drawings, paintings, illustrations and sculpture will provide the opportunity for this little-known artist's work to be brought once again to public attention.

Alison Bennett, January 2023

Works by Cicely Hey in public collections :

Drawings from the "Art Celebrities" exhibition :

National Portrait Gallery, London:

Francis Frederick Locker Birrell - NPG D34000

(William) Martin Conway, 1st Baron Conway of Allington - NPG D34001

Campbell Dodgson - NPG D34002

Thérèse Lessore (Mrs Sickert) - NPG D34003

British Museum:

Dugald Sutherland MacColl (donated by Tatlock) - 1933,0518.1

The Whitworth, Manchester:

Walter Sickert - D.2009.3

Jacob Epstein - D.2009.4

Samuel Alexander - D.2009.5

Roger Fry - D.2009.6

R.R. Tatlock - D.2009.7

Other works:

Figure in Stocks (mixed media) (1966) - Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading - 68/381

Portrait of Bob Hughes (terracotta) - Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea - GV 57.1362

24 Sketchbooks (1913- ) - National Museum of Wales, Cardiff - NMW A 21780-21785; NMW A 21986-21995; NMW A 25088-15095

Bird's eye view of the Tower of London, and surrounding area, as it appeared in 1597; poster produced for the Central School of Arts & Crafts from a survey taken by Gulielmus Haiward (colour lithograph, with Francis Ernest Jackson, 1919, for which Hey received £20) - British Museum - 1922,0311.28

EXHIBITIONS [incomplete]

Group exhibitions :

1928-70 (touring) The London Group

1929 No Jury Art Club, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London

1930 Young Painters' Society, London

1948 Colwyn Bay Sketch Club

c. 1949-70 Denbighshire Art Club, Colwyn Bay

1955 (touring) 2nd Exhibition of Contemporary Welsh Painting and Sculpture

c. 1956-68 North Wales Group

1957, 1959, 1960, 1961 Royal National Eisteddford of Wales

1963 International Puppetry Festival, Colwyn Bay

1964,1969 Shakespeare Festival, Stratford-on-Avon

2007-08 A Small World, Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading

National Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers and Potters

Society of Graphic Artists

Women's International Art Club

New English Art Club

One-person exhibitions

1933 Art Celebrities, Alex. Reid & Lefevre, London

1964 (touring) Period Figures, Geffrye Museum, London

2006 Drawings by Cicely Hey, Llanover Hall, Cardiff

The London Group exhibitions:

1923 Portrait

1923 Portrait

1924 Nude

1925 Siesta

1926 Valtournanch [sic]

1926 Interior; Nude

1927 The Red, Red Rose; The Green Scarf; Bath Time; The Professional

1928 Retrospective exhibition : The Model

1929 Jane at Home; Mrs P.; Through the Looking Glass; In His Garden; Nude

1929 Titivating; Indoors. Watercolours : In the Garden; Ayesha; The Empty Chair

1930 Dinner; Pin Mill; By the Mantlepiece. Drawings & Watercolours : Lily; The New Pet

1931 Listeners; Leisure; Cold Summer; In Her Bedroom; On Hampstead Heath

1932 At Her Mirror; Barbara; Dressing; The Professional; The White Dress

1933 Peace; Cabaret Girl; Weeping Nude; Nude

1934 Watercolours : Portrait; Dorette; Cabaret Girl; Cow and Calf; Roger Fry; Mother and Child

1935 Nude; The Good Companions; Angel Corner; Arkesden

1936 Portrait (drawing); 'Iris'; The Yard

1937 Sir Henry J. Wood (drawing)

1938 Near Hilton, Hunts; October; Four Sheep

------------------------------------------------------------------------

1949 Llechwedd; River Bank

1951 Harvest; Landscape

1952 Infant (terracotta)

1953 Bob Hughes (sculpture)

No Jury Art Club exhibition :

1929 Betty; Nellie; Trust

1st Exhibition of the Young Painters' Society

1930 Reflection

National Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers and Potters

1932 The Child

1934 At Her Dressing Table (watercolour)

Colwyn Bay Sketch Club exhibition

1948 'Sketches by Cicely Hey of The London Group'

Conway at Dusk (ink and wash); Professor S. Alexander (ink)

Denbighshire Art Society exhibitions

1952 Reclining Figure

1956 2 terracotta horse sculptures; painting by R. Evan Hughes depicting two of Hey's costumed figures

1957 Terracotta cow sculpture; 2 figures in 16th century costume

1965 Leviathon (wire sculpture); Costumed figure (16th century piper)

Works sold, as recorded by Artprice.com

1997 By the Mantlepiece

2019 Conway Castle (drawing/watercolour)

Manuscript sources :

Letters and telegrams from Sickert to Hey; letters from Thérèse Lessore to Hey; draft letter from Hey to John Woodeson; Hey's diary and notebook; Memories of Robert Rattray Tatlock and Cicely Hey by Margaret Clark (Sickert Family Collection, Islington Local History Centre, London). Further correspondence and papers relating to Cicely Hey are held at the National Library of Wales (AVA1/6).

Letters from Hey to David Garnett; letters from Hey to Rachel Garnett (McCormick Library & University Archives, Northwestern University, Evanston, USA).

With grateful thanks to the family of Cicely Hey, the Palliser/Roberts family, Madoc Roberts and to Mrs Janice Goble for their valuable contributions.

Endnotes:

[i] 1901 & 1911 censuses

[ii] Pensionnat Woodlands, 46 Boulevard Militaire, Ixelles, Brussels

[iii] Alistair Smith, 'Walter Sickert's Drawing Practice and the Camden Town Ethos', in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/alistair-smith-walter-sickerts-drawing-practice-and-the-camden-town-ethos-r1104369, accessed 16 July 2022.

[iv] UCL Calendar 1920-21 (exlibrisgroup.com)

[v] Denys Sutton Walter Sickert: a biography, pub. Michael Joseph, 1976

[vi] Matthew Sturgess Walter Sickert: a life, pub. Harper Collins, 2005

[vii] Hey designed a cover for Sidgwick's novel Restoration, pub. Sidgwick & Jackson, 1923

[viii] Baker, under her married name Ramsey, later set up a photography studio in Cambridge with Helen Muspratt and photographed many of their friends and members of the Bloomsbury Group who it may be assumed were regular visitors to Taviton Street.

[ix] Letter from Hey to Rachel Garnett. Undated but written shortly before Hey's marriage in 1924

[x] Letter from Sickert to Hey, August 1923

[xi] Matthew Sturgis, op.cit.

[xii] Walter Sickert: sketch for a portrait, BBC, 10 February 1961 (British Library, BL C653/20)

[xiii] Letter from Hey to Browse 8 June 1959

[xiv] The Times, 15 March 1930

[xv] The Times, 11 February 1932

[xvi] The Times, 16 February 1934

[xvii] Observer, 18 November 1934

[xviii] Scotsman, 14 November 1934

[xix] Hull Daily Mail 2 August 1937

[xx] Telegram from Sickert to Hey, 18 January 1929

[xxi] Hey and Tatlock sailed to Lisbon during the summer of 1922 and to Toulon over Christmas and New Year 1934-35

[xxii] Sylvia Gosse The Sempstress, 1913. National Museum of Wales NMW A213; Harold Gilman Interior with Woman Sewing, (study for Norwegian Interior), 1913. British Museum BM 1984, 1110.4

[xxiii] The Times, 13 March 1933

[xxiv] Letter from Sickert to Hey, 19 September 1934

[xxv] The Times, 2 July 1954

[xxvi] The Times, 2 July 1954

[xxvii] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 9 March 1933

[xxviii] Letter from Thérèse Lessore to Hey, 21 February 1933

[xxix] Margaret Clark Memories of Robert Rattray Tatlock and Cicely Hey, typescript, May 1994

[xxx] Letter from Thérèse Lessore to Hey 22 January 1942

[xxxi] Richard Shone Walter Sickert, pub. Phaidon, 1988

[xxxii] Draft letter to John Woodeson, 5 February 1973

[xxxiii] In his biography Matthew Sturgis describes the staging of Sickert's controversial painting The Raising of Lazarus (1929). Sickert had instructed Hey, modelling as Lazarus' sister, to express wonder at the miracle of Lazarus' brought back from the dead; but her acting ability, if any, remains unseen, Sickert having painted her from behind

[xxxiv] Hey later presented these drawings to The Whitworth

[xxxv] Lillian Browse Sickert, pub. Rupert Hart-Davis, 1960

[xxxvi] Letter to Hey from Browse, 5 June 1959 and Hey's reply 8 June 1959

[xxxvii] Misc. notes by Hey, 20 December 1976

[xxxviii] Alistair Smith, op.cit.

[xxxix] Wendy Baron Sickert, pub. Phaidon, 1973

[xl] Alistair Smith op.cit.

[xli] Letter from Sickert to Hey 24 June 1924

[xlii] BBC interview op.cit.

[xliii] Letter from Sickert to Hey 17 July 1929

[xliv] New York Times, 22 November 1936

[xlv] Inn Signs Through the Ages (1936), documentary presented by Fred Taylor

[xlvi] Manchester Guardian, 14 November 1936

[xlvii] Burlington Magazine, July 1929, 'The Date and Nationality of the Wilton Diptych'

[xlviii] In addition to Hey's design, two White Hart inn signs were lent, and another exhibited as a photograph, each with details of the inns to which they belonged. While none was illustrated in the catalogue, their present-day incarnations bear no resemblance to the unattributed design in the film still which may be assumed to be Hey's.

[xlix] Letters from Hey to Rachel Garnett 28 August 1931; Christmas 1938

[l] 1939 National Register

[li] Letters From Hey to David Garnett 3 & 19 November 1939

[lii] Curiously Ray's sister makes no reference to Hey in her diary entries for the time of Ray's death despite Hey being a close friend of the family and a point of contact for news of her sister's declining health (Frances Partridge Diaries 1939-1972, pub. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000)

[liii] Letters from Hey to David Garnett 9 March 1941; Christmas 1941

[liv] Letter from Frances Partridge to Wendy Baron, 26 February 1990 (Sickert: Paintings, eds. Wendy Baron & Richard Shone, pub. Yale University Press, 1992)

[lv] Wales Today: Cicely Hey, Model Maker, Colwyn Bay BBC, 16 December 1965, (BBC Rewind online archive). The National Library of Wales holds an HTV Wales film reel of Y Dydd [The Day] featuring Cicely Hey and her model figures, broadcast 27 January 1965

[lvi] Founder of the Little Angel Theatre in Islington, London

[lvii] V&A Museum https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-history-of-puppets-in-britain, accessed 3 October 2022

<

Gerald Cooper's 'Allegory on The Three Ages of Man'

The artist's rediscovered 1923 Prix de Rome scholarship submissionThe Prix de Rome Scholarship offered by the British School in Rome was the most prestigious award an art student could win during the interwar years and was a highly contested annual event. The 'Scholarship in Decorative Painting' as it was described until 1929 invited the most able students from the best art schools to compete for the £250 per annum (over three years) prize. In 1923 one of the hopeful applicants was Gerald Cooper who was then in his final year at the Royal College of Art.

Gerald Cooper (1898-1975) - Allegory on The Three Ages of Man, 1923

After serving as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps during WW1, Cooper studied at the RCA from 1920 to 1923 where he was recognised for his exceptional draughtmanship - winning the Drawing Prize jointly with Phyllis Dodd. His artistic outlook was therefore formed by very much the same kind of training as that undergone by the generation that emerged as major figures in the years before and after the Second World War - one based almost exclusively on drawing. At the relatively mature age of 25 and as one of the star pupils in a very talented year he must have felt optimistic about his chances of winning the coveted Rome Scholarship. However Cooper's monumental efforts were to no avail as he was not awarded the prize leaving him to wrestle with feelings of disappointment and rejection. This perhaps explains why the canvas was rolled up by the artist and left discarded in a dusty corner of his studio thus remaining forgotten and unappreciated for nearly a hundred years.

The recent rediscovery of Cooper's large scale submission is a poignant reminder of the talented artist's early ambition - a precious moment in time encompassing the sensations of youth when all seemed possible. The work itself is also engagingly evocative of the style and atmosphere of England in the early 1920s. Although inspired by classical themes and aesthetic principles, the painting is full of lovingly rendered details of 1920s fashion and everyday life - underpinned by an awareness of the social nuances of that period. A striking Edwardian elegance, most famously captured by Augustus John, also looms large in the painting.

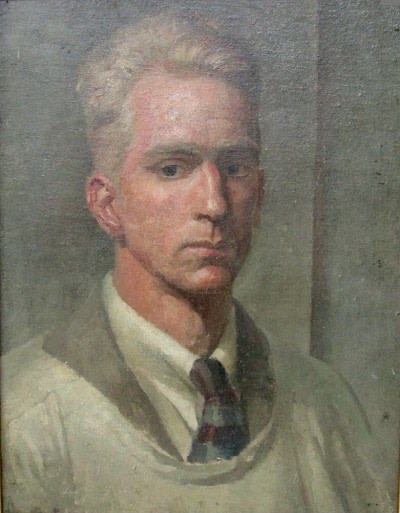

Gerald Cooper - Self Portrait, c. 1930

Cooper became a member of the full-time staff at the Wimbledon School of Art in 1925 becoming principal in 1930 - a post he held until 1964. This wholehearted commitment to teaching no doubt restricted his own personal artistic practice and he was content to devote his technical skill to meticulous flower paintings very much in the Dutch Old Master tradition. These works proved commercially successful and were widely admired, but they lacked originality and were certainly no comment on the time in which he lived. He was instrumental in building the reputation of the Wimbledon School of Art and championed the development of the new art school building in Merton Hall Road.

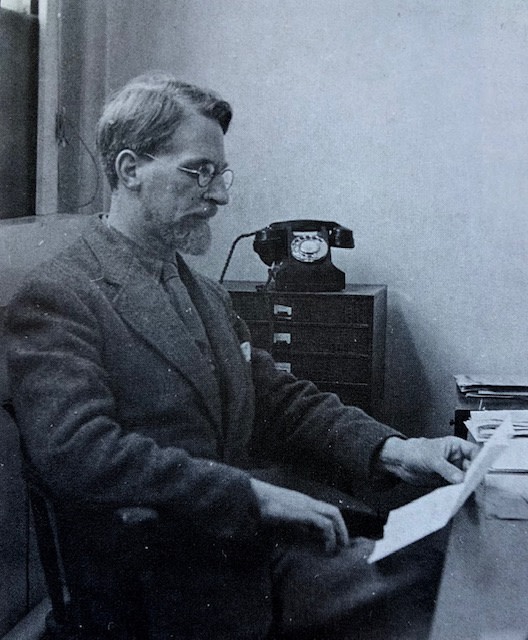

Gerald Cooper photographed at the Wimbledon School of Art, Merton Hall Road in 1940

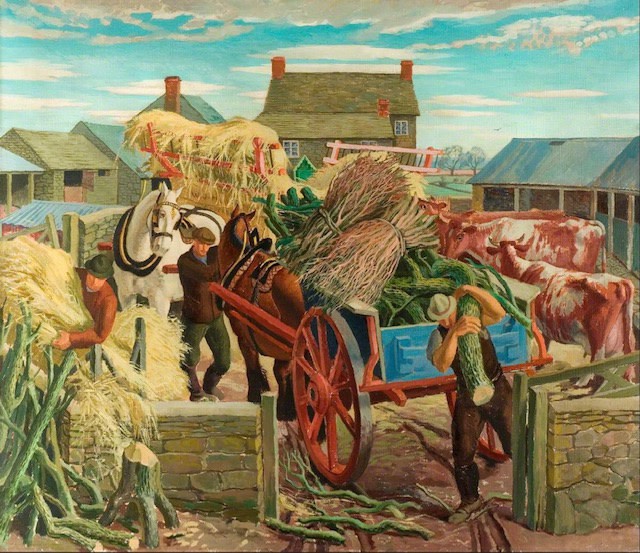

Cooper did not abandon figurative painting completely, producing a memorable series of farm paintings during the 1930s that again demonstrated his talent for large scale figurative compositions. His painting Winter from 1935 admirably demonstrates this quality and was purchased by the Corporation of Stoke from the RA summer exhibition - a contemporary review of the time noted how the work, 'Brilliantly captures the atmosphere of harvest time on the farm'. Cooper's considerable achievements in this genre were recently recognised in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, True To Life - British Realist Painting in the 1920s & 1930s.

Gerald Cooper (1898-1975) - Winter, 1935, (Corporation of Stoke)

The rediscovered Prix de Rome canvas with its impressive scale and refined style offers a tantalising glimpse of the artist that Gerald Cooper could have become had his career after the Royal College not been monopolised by teaching and the burden of financial necessities.

Eileen Agar's 'Obelisk of Satisfied Desire'

An exceptionally rare surrealist sculpture not seen since the artist's 1985 retrospective at the New Art Centre, London

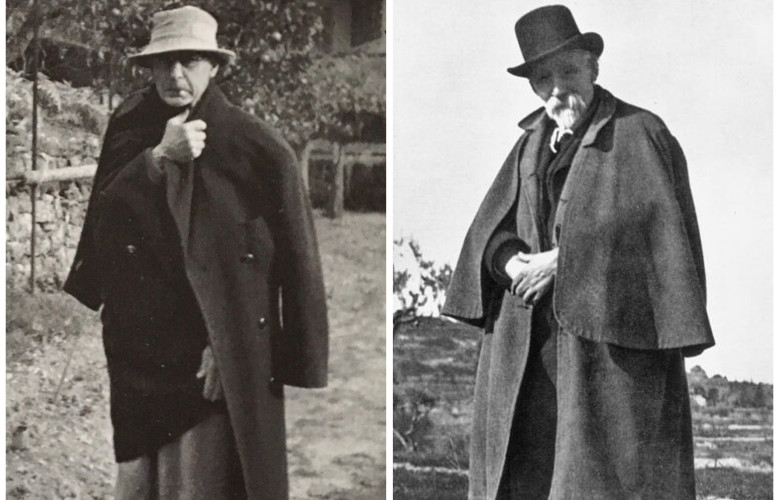

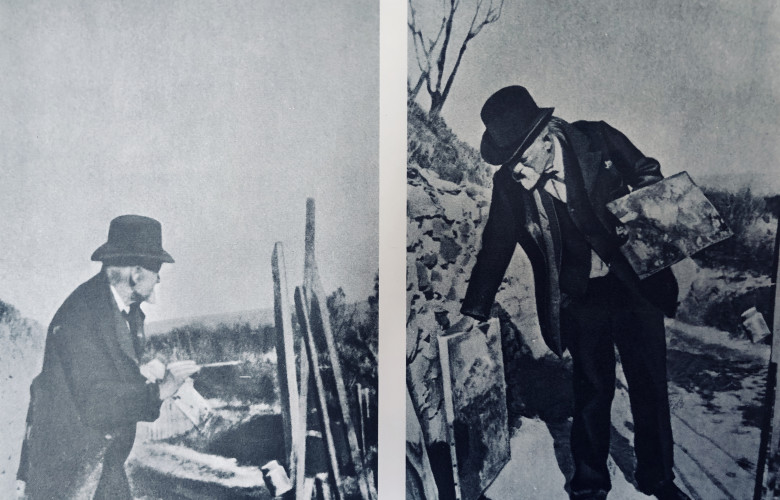

Paul Cezanne painting at Aix, c. 1905

Paul Cezanne painting at Aix, c. 1905