Cezanne settled in Aix in 1890, living at the Jas de Bouffan with his mother and sister while his wife and son moved to an apartment in the town the following year. His father's death in 1886 had left him without financial concerns and by the 1890s Cezanne's work and its significance was beginning to be recognised, with Vollard's momentous exhibition of his paintings and drawings opening in Paris in November 1895.

Paul Cezanne, Rochers et arbres, 1890-95

Pencil and watercolour. 46 x 35 cms. (The Court Gallery)

Executed around 1890-95, the present work probably takes its subject from a path in the forest of the Château Noir, through which he often passed on walks away from Aix towards Mont Sainte-Victoire, which is visible in the distance. Between 1890 and 1902 Cezanne rented storage space for materials at the Château Noir property, and he documented various stages along the paths that led through the adjacent forest in numerous paintings and drawings.

Motifs similar to Rochers et Arbres appear in a number of works during this period, bringing together two themes which clearly preoccupied Cezanne at this time, firstly the complex patterns of interweaving branches and, secondly, the natural and man-made rock formations that he found around the Bibémus Quarry and the caves near the Château Noir. Françoise Cachin notes, 'From the Île de France landscapes of the 1870s to the paintings of the Bibémus Quarry and the environs of the Château Noir from the very last years of his life, Cézanne obsessively explored motifs of trees, forests, thickets, screens of foliage, and leafy masses, all viewed from a person's average height, with no trace of sky and no depth of field, images of a nature whose vitality is almost suffocating, whose colours are organised in green patches held in place by the rigorously drawn lines of tree trunks.'1.

Paul Cezanne, Rochers et arbres, 1890-95, (detail)

Rocks and Trees departs slightly from this by suggesting the landscape beyond the forest, where the path drops down across the sloping terrain to a plain that rises up again towards the mountain, whose striking profile seems to mirror the rocks in the foreground, creating unity across the sheet. Subject matter was crucial to Cezanne, despite the increasing abstraction of his watercolours in this period. The Royal Academy exhibition, Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings, originally scheduled for June 2020, notes that 'his fascination with rock formations led to some of his most remarkable paintings and watercolours.'2

Yet despite Cezanne's interest in the physical nature of rock forms and the 'accurate transcription of nature'3, which the repeated use of motifs arranged around this path confirms, the physical world often becomes only a necessary part of the ambition of his art; Walter Feilchenfeldt notes of his watercolours and drawings that 'however much they may still possess figurative elements [they] are less concerned with depicting a motif than with a composition shaped by it'.4

This relationship between the image and the original motif is explored in depth by Erle Loran, a number of whose own photographs of the sites in the Forest of the Château Noir where Cezanne worked, taken in the late 1920s when he occupied Cezanne’s studio near Aix, bear close comparison with the present work. He wrote that ‘Cézanne’s landscapes provide the most gratifying pictorial experience of nature; atmosphere and light are expressed with a formal structure comparable to Giotto’s’,5 and Loran’s analysis of these structures and Cezanne’s manipulation of elements of each motif is illuminating in the context of the present work, with its tightly organised space and inter-relating forms and planes.

Paul Cezanne, Rochers et arbres, 1890-95, (detail)

There is an intriguing psychological element in the present work's scope, its concentration on the details of the foreground to the extent that Cezanne creates a path along which we can imagine walking, while also maintaining a constant reminder of the goal beyond, the motif that dominated these later years. In holding in balance the two of these, the human scale of these almost imperceptible physical and visual details memorised through these daily walks as well as the monumental scale of the mountain that seems to represent something beyond human attainment and understanding, there is an intriguing insight into Cezanne's concerns as an artist and the constant creative decision-making that characterised him.

Lawrence Gowing wrote that '[the] watercolours of Cézanne are as elusive and unaccountable as anything in art…Tentative sequences of diluted colour drift across empty paper for purposes that remain elusive'6. The present work maintains that mystery; the application of patches of colour is minimal and precise, establishing tonal relationships along certain contours of the drawing. It recalls Picasso's words: 'Hardly has he applied a spot of colour, and the painting is there.'7

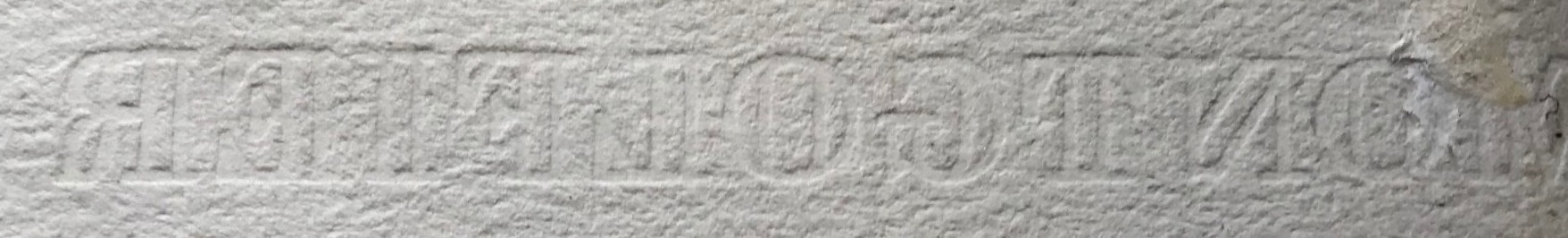

The watermark on the verso of the sheet is from the Canson et Montgolfier paper mill at Vidalon-lès-Annonay, described by Fabienne Ruppen as 'one of the most prestigious producers of a wide range of high quality paper in Cezanne's time'.8 The same watermark appears to be on the verso of the Apples, Bottles and Chairback (c.1904-06) in the Courtauld Gallery, London, and also Study of a Nude, c.1885, in the Fogg Museum, while Fabienne Ruppen also notes that a number of watercolours on Canson et Montgolfier paper with a slightly different watermark depicted 'the sandstone cliffs above the château and in the adjacent quarry of Bibémus'.9

Canson et Montgolfier watermark

Cezanne's drawings and watercolours quickly became appreciated by artists, collectors and critics, in their own right and for their own very distinctive qualities. In 1907 Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, 'The watercolours…are very beautiful. They show as much assurance as the paintings and are as light as the others are massive. Landscapes, very slight pencil outlines upon which falls only here and there, as though to emphasise or confirm, an accident of colour, a series of washes, admirably arranged and with great sureness of touch: like the echo of a melody'.10

We are very grateful to Dickon Hall for preparing this article.

Notes

[1] Cachin, Françoise, Cézanne, Tate Publishing, London, 1996, p.378

[3]Cézanne, London, 1996, p.368

[4] Felichenfeldt, Walter, ‘Paul Cezanne: The Introduction of a New Art’, Reconstructing Cezanne, Luxembourg and Dayan, Ridinghouse, London, 2019, p.7

[5] Loran, Erle, Cézanne’s Composition, University of California Press, Los Angeles and London, 2006, p.118

[6] Gowing, Lawrence, Watercolours and pencil drawings by Cézanne, Northern Arts and Arts Council of Great Britain, 1973, p.5

[7] Parmelin, H., Picasso dit…, Paris, 1966, p.85, quoted in Felichenfeldt, Walter, ‘Cézanne: Finished – Unfinished’, By Appointment Only, Thames and Hudson, London, 2006, p.272

[8] Ruppen, Fabienne, ‘Tackling Cezanne’s paper: On the Reconstruction of Loose Sheets’, Reconstructing Cezanne, p.23

[9] Ibid., p.26

[10] Letter from Rainer Maria Rilke to Paula Modersohn Becker, 28 June 1907, in Rilke, Briefe aus den Jahren 1906-07, quoted in ‘Cézanne: Finished – Unfinished’, By Appointment Only, p.276