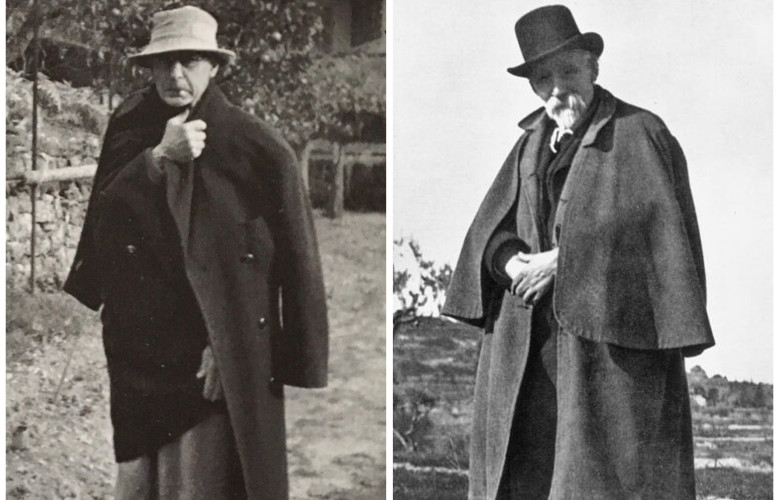

Pierre Bonnard never met Paul Cezanne, but his admiration for the older artist is demonstrated by his inclusion in Maurice Denis's 1900 painting Homage to Cézanne. The Nabis' interest in Cezanne, whom Denis had visited in Aix-en-Provence, lay as much in his radical and pioneering approach to being an artist, as much as any visual similarity that their work bore to his. Of all this group, whose connection was only loosely maintained after the 1890s, it was arguably Bonnard whose solitary later life and continual experimentation brought him closest to Cezanne.

Both artists were born in the country, Cezanne in Aix and Bonnard in Normandy, and moved to Paris to pursue their careers as artists, having both, by coincidence, abandoned the legal careers their families had encouraged. Unlike Cezanne, Bonnard found sustained early recognition, as an illustrator as well as a painter, and also was also soon part of a group of like-minded contemporaries, but both artists were gradually drawn away from the city and spent most of their last years living and working in the south of France.

Paul Cezanne, Study of Madame Cezanne and Paul, (verso), 1873, The Court Gallery

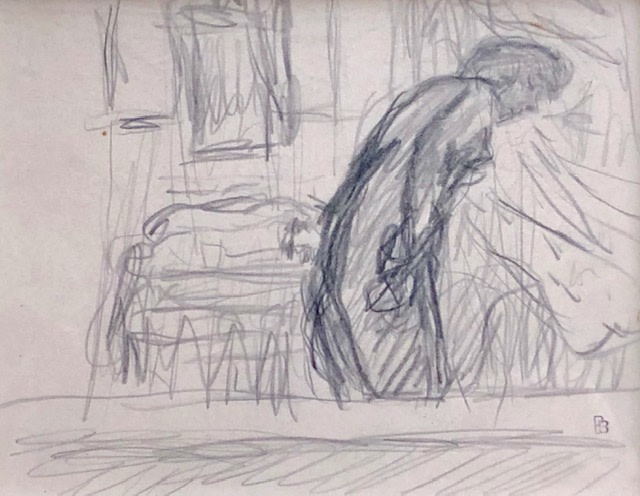

For Cezanne and Bonnard their wives were a frequent subject of paintings and drawings, and both relationships have become known for their complexity There is intimacy as well as mystery in Cezanne's many drawings of Hortense and his son Paul, with two or three sketches often occupying the same sheet. Bonnard was in a relationship with Marthe, like Hortense from a very different social background to her husband, for some years before they were married, again as with Cezanne and Hortense, and Bonnard's obsessive recording of her bathing almost becomes a metaphor for her elusiveness within his work. The sense of absence and mystery is expressed through her constant yet unchanging presence.

Pierre Bonnard, Marthe in The Bathroom, c. 1920, The Court Gallery

These two watercolours, both painted in the south of France around four decades apart, have a number of interesting points of comparison. Firstly, both works are on paper from the same manufacturer, Canson et Montgolfier. This company had made paper of a high quality that was popular with artists from Ingres to Degas and Matisse and their watermarks have recently been used in significant academic research to date works by Cezanne and to make connections between works on sheets he had divided. Fabienne Ruppen notes that a number of watercolours on Canson et Montgolfier paper with a slightly different watermark depicted 'the sandstone cliffs above the château and in the adjacent quarry of Bibémus'1, close to the location of the present work.

Paul Cezanne, Rochers et Arbres, c. 1890-95, The Court Gallery

The most obvious connection between the works is their subject. For Cezanne and for Bonnard, trees were a crucial motif within their later work. The opportunities they offered the former as structural elements within a composition, often becoming highly abstracted, are clearly explored in Rochers et Arbres, while for Bonnard they perhaps acted in a metaphorical role as well as allowing him a greater complexity in the colour and interlocking shapes of his later landscapes in particular. One anecdote records Bonnard paying a stranger not to cut down an ancient poplar tree,2 and his final painting was of a single almond tree in blossom, so they were clearly of great personal significance.

Cezanne settled in Aix in 1890, living at the Jas de Bouffan with his mother and sister while his wife and son moved to an apartment in the town the following year. His father's death in 1886 had left him without financial concerns and by the 1890s Cezanne's work and its significance was beginning to be recognised, with Vollard's momentous exhibition of his paintings and drawings opening in Paris in November 1895.

Executed around 1890-95, the present work probably takes its subject from a path in the forest of the Château Noir, through which Cezanne often passed on walks away from Aix towards Mont Sainte-Victoire, which is visible in the distance. Between 1890 and 1902 Cezanne rented storage space for materials at the Château Noir property, and he documented various stages along the paths that led through the adjacent forest in numerous paintings and drawings.

Pierre Bonnard, Landscape with Trees, Le Cannet, c. 1930, The Court Gallery

Intriguingly Bonnard's Landscape with Trees also seems to relate to the routine of his daily life as a painter. In 1926 he purchased the Villa 'Le Bosquet' at Le Cannet, near Cannes, and he often worked in his studio there until his death in 1947, while continuing to spend time in Paris and Normandy, where he owned a house at Veronnet. The turning path in the foreground of the present work, the very specific arrangement of the trees on the hillside and the suggestion of a building behind the trees at the centre right, are all remarkably close to a photograph taken in 1945 by Henri Cartier-Bresson of Bonnard standing on the path leading beside the garden to his house.

The watercolour is notably consistent with Bonnard's later landscapes in compositional terms; the extreme edges of the sheet are brought into play with intruding branches and emphasise the strong pattern within the composition, as well as connecting the immediate foreground plane with the blue sky and distant trees. As with many of his later landscape paintings, colour is used as part of an overall harmonic conception rather than to define more clearly various elements of the image.

Both works demonstrate the importance of drawing for these artists in the analysis and organisation of a motif. While Bonnard's line is full of energy and demonstrates his enduring passion for nature and its power to provoke him with new discoveries even in a familiar scene, Cézanne sought order and solidity, an 'atmosphere and light…expressed with a formal structure comparable to Giotto's',1 as is evident in the tightly organised space and inter-relating forms and planes of the present work.

Colour is introduced in a conscious interplay with the substantially worked drawing in each case. While Bonnard evokes the visual complexity and the particular mood of the scene in front of him at a particular moment, Cezanne's highly deliberate application of patches and lines of colour establishes tonal relationships and fixes certain points in space, as well as suggesting the visual sensation of the artist. For both men colour became a crucial element of their painting after they moved to the south and the distinctive light that drew them there transformed their use of watercolour.

The circumstances of each work adds a highly personal quality. These motifs were highly familiar to both artists and they probably considered the various elements of the image on the way to a day's painting, or at the end of a day's painting. The very direct and instinctive nature of the medium that they chose for these works, each completed to the necessary point for their purpose, adds to this sense of immediacy and insight.

Notes

1. Ruppen, Fabienne, 'Tackling Cezanne's paper: On the Reconstruction of Loose Sheets', Reconstructing Cezanne, p.26

2. Albert Kostenevitch, 'Bonnard and the Nabis', Parkstone Press International, New York, 2005, p.56

3. Loran, Erle, Cézanne's Composition, University of California Press, Los Angeles and London, 2006, p.118