Doris Hatt was one of the most distinctive and advanced artists working in the west country during the first half of the twentieth-century. Born in 1890 and from a well-known and affluent Bath family, she received a privileged education in London, Vienna and Paris, studying in London at the Royal College of Art and at Goldsmith's College, but it was her visits to Paris in the early 1920s that were to inspire her artistic direction. Having initially been influenced by Paul & John Nash and the Romantic English landscape tradition - she was soon captivated by the modern Paris School, particularly the works of Braque, Léger and Picasso. She began exhibiting with the Clifton Arts Club in 1921 where fellow exhibitors included Wyndham Lewis and the Bloomsbury artists Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. Even in this company the strength and quality of her paintings were quickly noticed prompting Albert Rutherston to write of her 'distinction' and her 'curiosity and conscience'. However it was the intoxicating atmosphere of Paris during the 1920s with its euphoric optimism for the speed and dynamism of the new machine age that was to have the most profound impact on her life and work.

Hatt first studied in Paris in 1922 and was drawn to Léger's Free School where she was able to develop her own personal take on Cubism bringing a uniquely English quality to an international movement. She became steeped in the writings of Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (more commonly known as the architect Le Corbusier) and their modernist doctrine of Purism. This was the new gospel for the thrilling age of science and mechanization which rejected early Cubism's fragmentation of reality in favour of a monumental style that celebrated the production line and the standardization of objects for modern life. In painting, the most dominant and successful exponent of the new utopian creed was Fernand Léger who had experienced the horrors of the trenches first hand but held a determined belief in the possibility of a better world and thus embraced the representation of reality in heroic terms. Hatt was also certainly influenced by Léger's commitment to Communism - a political ideal that was to become the cornerstone of her life.

Returning to Clevedon in the late 1920s she opened her studio once a week offering free art classes to locals in her desire to educate and open minds to the new developments in art. She delivered regular public talks on art in a brave attempt to communicate her ideas to a wider public as she did not want to 'live in a vacuum' and feel isolated from her community. During the 1930s a family inheritance enabled her to commission the building of a starkly modern house and studio according to Bauhaus principles where she lived and worked with her life-long partner, the weaver Margery Mack Smith. Her home became a centre for radical activity both in art and politics and was a meeting place for like-minded people throughout the region. Her Sunday parties became legendary - the regular gathering of her communist friends caused a stir amongst Clevedon's 'polite' and predominantly conservative society.

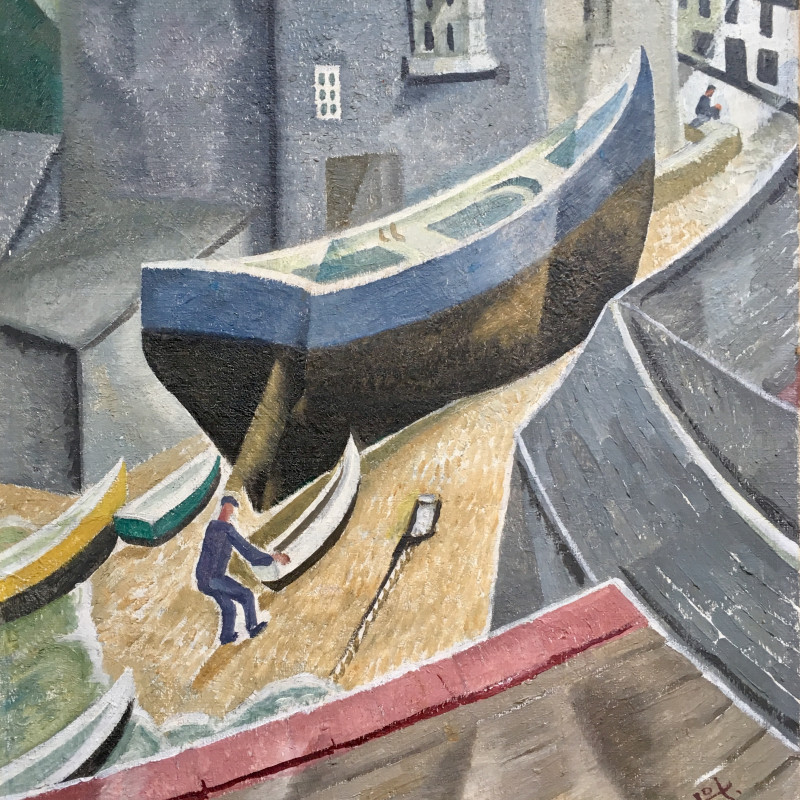

Hatt developed a painting style that was meticulous in its planning and execution. Her great mantra being 'to simplify and at the same time intensify' with her guiding aim to present only the essential elements in her compositions whilst rigorously discarding all that was superfluous to the intended design. In her own words this disciplined process meant that 'order' had 'been brought out of chaos - that life after all is not so difficult as it seems. This will give you a sense of power and well being as you study the picture.' Yet as her friend and supporter Professor Peter Millard observed - 'There was nothing brutal about Doris's paintings, nothing raw... It is typical of English artists to take an international style, and then to soften and lyricize it, giving it an essentially English sensitivity.' Indeed there is a strong Romanticism in Doris Hatt's work which pays homage to the ancient traditions of painting.

A highly political feminist, Hatt became a member of the Independent Labour Party soon after the First World War, but in response to the rise of Fascism during the early 1930s she joined the Communist Party and was a tireless activist even standing for election as a Communist candidate in Clevedon during the 1946 local elections. She began her election leaflet with the following statements:

I believe that Clevedon Council cannot be representative of the majority of the Clevedon people unless there is an increase of Councillors with working-class sympathies.

I think also that Women should be represented on the Council. At present there are no Women Councillors.

According to Professor Millard, 'Doris Hatt's communism was gentle and kind, and suffused with solid middle-class virtues.' Her political passions were guided by an empathy for others and a belief in fairness and equality - these were essentially humanitarian concerns with the noblest of intentions. She was also widely and affectionately known in Clevedon for her regular visits round the local pubs selling the Daily Worker and she remained staunchly loyal to the Communist cause right up to her death in 1969. In the light of Picasso's membership of the Communist Party, she was formally invited by the Soviet Embassy as the Communist representative to the opening preview of the great Picasso exhibition at the Tate Gallery, London in 1960.Much honoured by the invitation, she attended the private view dressed in traditional Spanish costume, borrowing a long black dress and wearing an old mantilla leading the the press to believe that she was a relative of the great artist.

During the last twenty years of her life Hatt divided her time between Clevedon and her partner's cottage in Watchet and these two places provided many of the subjects for her paintings and coloured linocuts. Every year she would travel abroad favouring destinations in the South of France and Spain and she often stopped off in Paris to keep abreast of the very latest developments. Her paintings gained acceptance in Paris and she exhibited regularly at Galerie Zack and her work was favourably reviewed in La Revue Moderne. Although she was a prolific exhibitor in the south west, particularly at the RWA and the Clifton Arts Club, she was never inclined to secure a regular London dealer and perhaps as a result of this she is not as widely known today as she deserves to be. She lived a courageous and inspirational life, full of passion, commitment and individuality which is richly evident in her powerful, life-affirming, paintings.